When looking at the American vehicles in our collection, you may notice that they have quite a number of markings on them. To those who do not know how to read them, they may just look like a series of cryptic shapes, numbers and letters. To help you understand these markings, let’s take a look at our M3A1 Half-track to get a better understanding of them.

First, let’s take a look at the front bumper. The markings here are split into four groups. The first group is located on the passenger’s side of the vehicle, and reads “2△.” This denotes the highest overall unit the vehicle belongs to. The △ represents an armored division, as the triangle was the symbol of Armored Force. Next to that is “41-1,” which shows the regiment and battalion.zed a single .50 M2 for self-defense purposes.

On the driver’s side, groups three and four are read as one, which on our half-track reads as “D-9.” These two groups show the company the vehicle belongs to, as well as its

position within a road march. Putting all of this together, we now know that this M3A1 is the 9th vehicle belonging to Dog Company, 1st Battalion, 41st Armored Infantry Regiment, 2nd Armored Division.

Our M3A1 is the 9th vehicle belonging to Dog Company, 1st Battalion, 41st Armored Infantry Regiment, 2nd Armored Division.

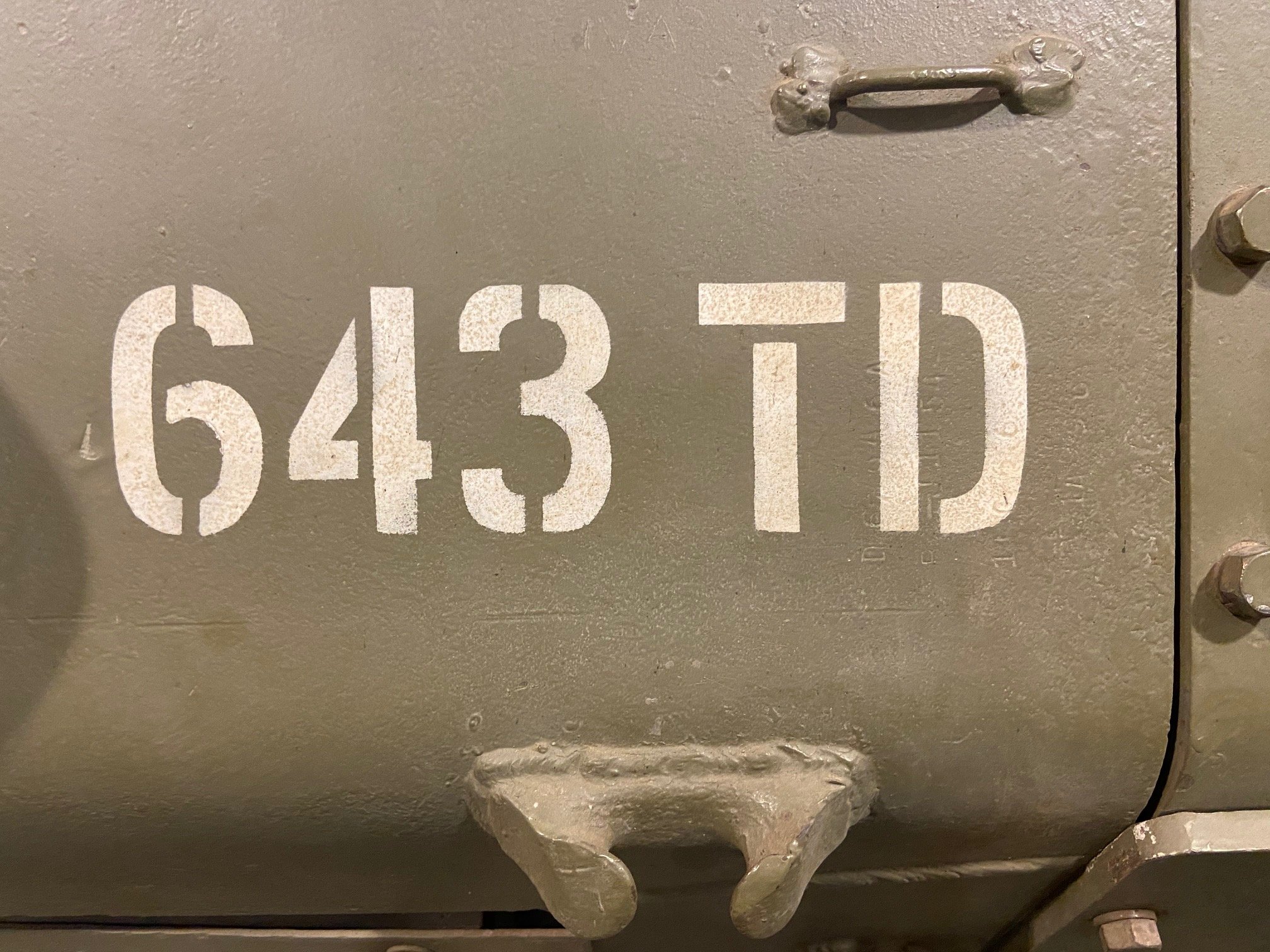

For vehicles which do not belong to an armored division, or are independent from them, they use different markings to denote that. Our M18 for example, drops the first group

and only has the second group on its front left fender reading “643 TD” to show that it belongs to the 643rd Tank Destroyer Battalion.

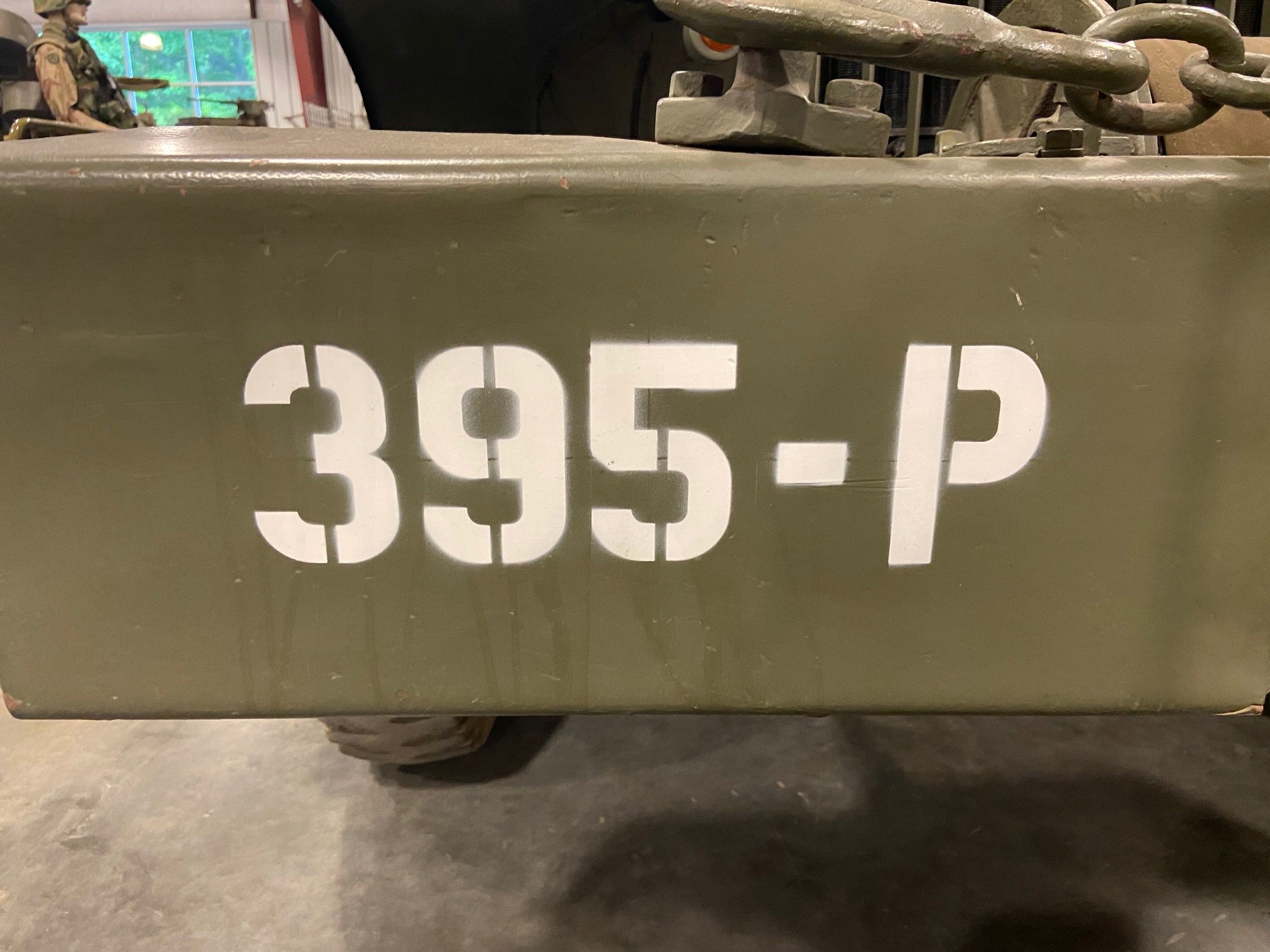

Our CCKW similarly has only the second group to show that it belongs to the 395th Military Police Battalion.

The final set of markings seen on U.S. Vehicles during the war are what are referred to as “usage markings.” These markings were related to various aspects in the vehicle’s day-to-day operations. The first and perhaps most well known of these usage markings is the Bridge Classification Plate. The purpose of these plates was to allow a vehicle crew, MP, or engineer to see at a glance whether or not a vehicle was too heavy for bridges. Bridge Classification Plates consisted of a yellow circle eight inches in diameter with the average weight of the vehicle type placed in the center. For example, M4 Medium Tanks were classed in the 30 to 36 ton weight range, which accounted for differences in the weight between vehicles. Some vehicles, like Jeeps and 2 ½ Ton Trucks, had Bridge Plates with two values on them: one for the weight of the vehicle, and another for the weight of a trailer if it was expected to tow one frequently. The Museum’s M25A1 Tank Transporter, for example, has a bridge classification of 24 for just the M26A1 tractor, and 115 for the tractor and trailer fully loaded.

.jpg?width=2048&name=104282434_354418245537603_291289003132222670_n%20(1).jpg)

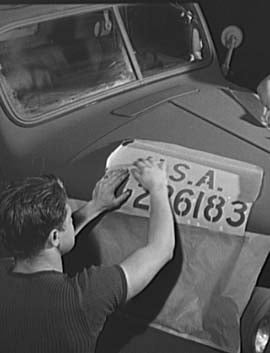

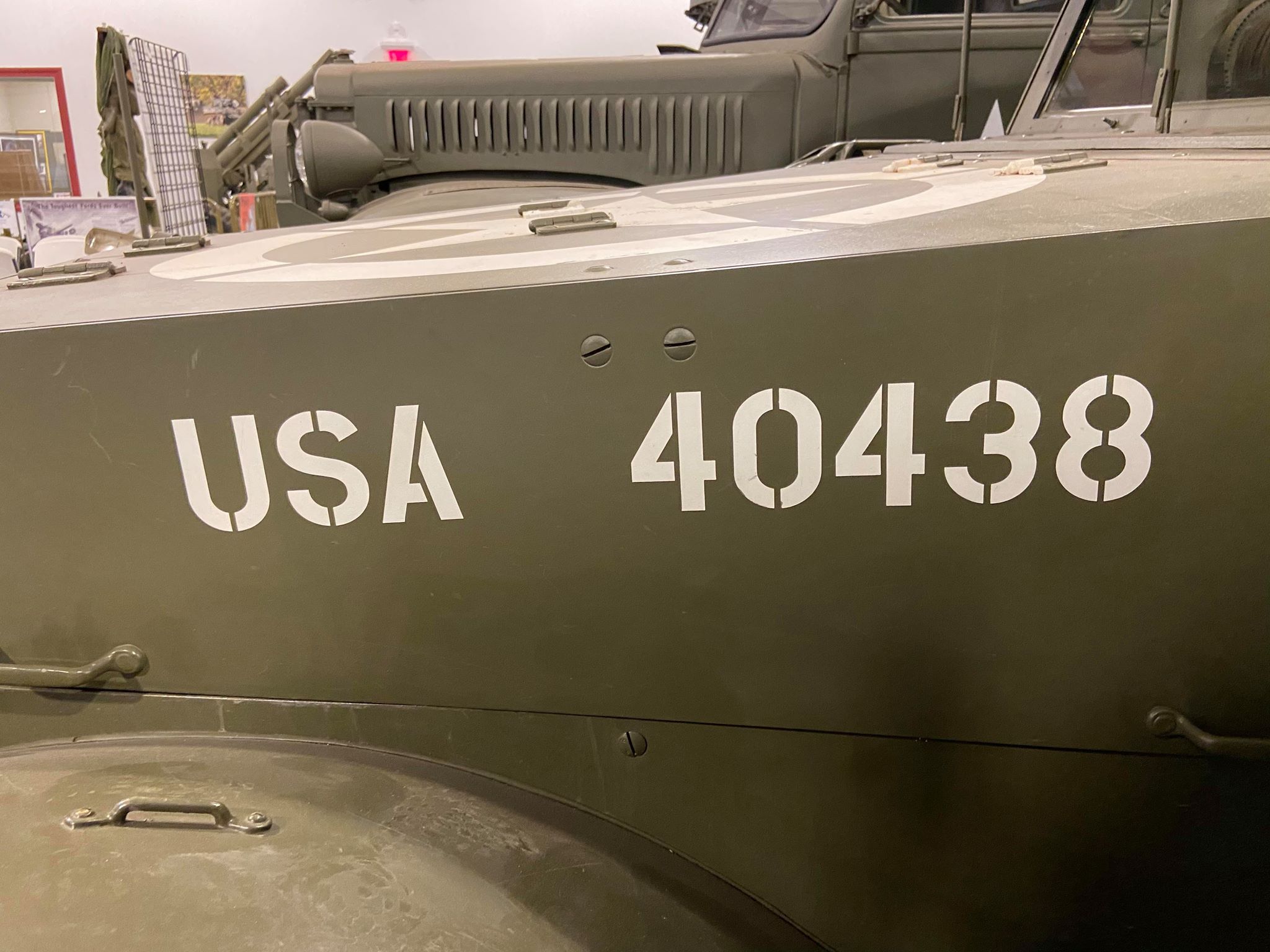

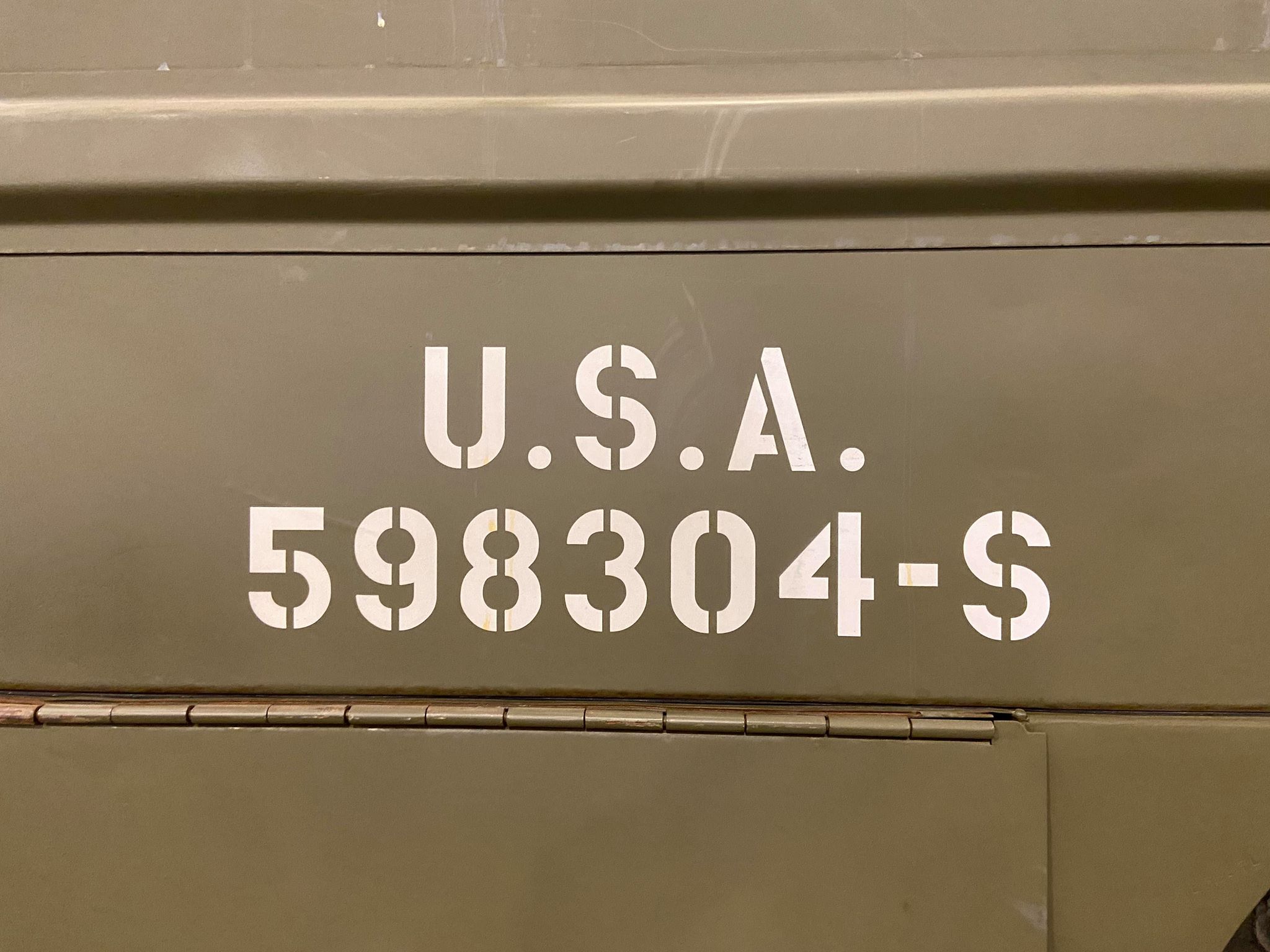

Registration Numbers were used to organize types of vehicles into general categories. These were painted on the sides of the vehicle, usually on the hood if it had one. The Registration Number was preceded by either a “U.S.A.” or “U.S.” marking, followed by a two digit code that showed the category the vehicle belonged to. Tanks were grouped under “30,” while other tracked vehicles like High Speed Tractors and half-tracks were “40.” The remaining digits were the individual vehicle’s production number according to Ordnance records. Some vehicles had a -S after their registration number to indicate that they were fitted with special radio interference suppression equipment.

As many of the vehicles were going to be stationed in the United Kingdom prior to and after the invasion of Northwest Europe, vehicles that lacked direction indicators were marked to notify the public that the vehicle was left hand drive. This was a pre-emptive safety measure, as the U.K. is a right-hand drive country. Another safety measure was writing the maximum road speed of a vehicle in miles-per-hour on its rear. The rear of a 2 ½ Ton Truck stationed in the U.K., for example would, would read:

CAUTION

LEFT HAND DRIVE

NO SIGNAL

MAX SPEED

40 MPH